Hello everyone! I’m so excited to announce we are going to have a monthly podcast in this space! This was on my radar for later, but because so many people are contributing I can now pay a modest stipend to interview autistic/adhd folks I think you all would love to hear from. Please continue to support the newsletter/share about it so we can keep this going!

The focus of the podcast will be on highlighting how people from different lived experiences masked/mask their autism in religious settings, and I recommend downloading the substack app if you haven’t already for easy listening (or just click play wherever you are reading this). You will also find the transcript of the chat below in case you aren’t an audio learner.

Next week we will be back to our regularly scheduled posts, but you can always become a paid subscriber and get in on our awesome Friday conversation threads and meet some likeminded folks (it seems like a LOT of us are into theology, cults, native plants, and animals!)

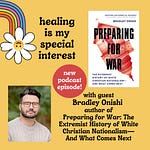

The first guest is a good one! I just recently heard Richie X on the Back to the Garden podcast and feel in love—with their voice, their deep insight, and sense of humor! Richie is Black, queer, and has quite the history with religion. They have their own podcast called Surviving Fundamentalism and I highly recommend starting at the beginning and listening along. It’s a picture of someone discovering their neurodivergence and how religion played a part in them not fully being able to be themselves.

Richie X recently started their own substack and it’s amazing! Head on over there, subscribe, and follow along for more insights (I could literally listen/read Richie talk about James Baldwin ALL DAY LONG).

Thanks for being here and giving me the freedom to do exactly what I am interested in, which is talk to other late-diagnosed autistic people about religion and masking! What a freaking gift.

TLDR: Danielle talks with Richie X, host of the Surviving Fundamentalism podcast, about their life and background in the Black Pentacostal church and their journey of unmasking and discovering their own neurodivergence and queerness.

You can follow them @RichieAtItAgain on Twitter and Instagram.

God is My Special Interest Episode 1 Transcript:

Danielle: [00:00:00] Okay, welcome to the first ever podcast for, uh, God is My Special Interest, a place where we talk about late diagnosed neurodivergence and, uh, the intersection of faith and spirituality. And specifically for my context, Christianity, but I'm really excited, because I wanna do a podcast where I get to interview some people who, uh, may or may not have had really different experiences than me, but they're people who are also understanding their neurodivergence later in life and have some connection to faith.

So, I think today is very exciting. I'm talking for the first time ever to someone I just met, and that is Richie X. And I first heard Richie X on a podcast like two weeks ago, maybe. And then I've been listening to Richie's podcast. To be perfectly honest, I thought I would listen to your podcast Richie and just learn a lot, you know, and just like, you're very different from me, but we have a few similarities as far as neurodivergence, all that [00:01:00] stuff.

And then I would just get lulled into just feeling like I was listening to somebody I'd known for a really long time. Just the way you talk on your podcast is so inviting. There's a beautiful cadence to it. I mean, a lot of the stuff you say is surprising though. So it's such an interesting push and pull. I'm like, I feel warm and safe and then also like, whoa, okay, I just learned something really interesting. And then you're back to this like warm and safe feeling. So I just loved, I loved the way your podcast made me feel. So I just wanna tell you that, um, before we get started.

Richie: Thank you.

Danielle: And I wonder if you could just tell the listeners just a real quick introduction to yourself.

Richie: Well, you know, when the other podcast I was on that quick introduction turned into an hour. Uh and, and funny, I asked them, why would you let me talk that long? They're like, we just wanted you to talk and I'm like, no, you gotta ask questions. Um, okay,

Danielle: I'll do that for you. [00:02:00]

Richie: I, uh, so, okay. So, I am Richie X.

I am the host of Surviving Fundamentalism, the podcast where if your God ain't bigger than your Bible, then you most likely probably will have a problem with this shit. And so, I, um, quickly, I am an ordained minister. I was, uh, licensed to preach at, at a very young age, at 13 years old. I preached for a long time, did a lot of evangelism, uh, in the Pentecostal church, uh, specifically the, uh, apostolic Pentecostal church, um, which is basically oneness or Unitarian, if you will. Um, and yeah, so I, I mean, and so I, you know, I went to college and so I have a degree in [00:03:00] English, uh, writing and political science from William Patterson University, New Jersey, and now I work for the government.

Danielle: Oh, really? Okay. Wow. And when did you start to understand neurodivergence? I don't think I kind of caught your timeline there, but how recent is this for you?

Richie: Oh yeah. Um, so. That's uh, quite an interesting journey. I'm gonna jump really fast from first grade to where I am now really fast. In the first grade, my mother was told to have me tested.

I was being raised as a—I'm also non-binary—I was being raised as a, you know, Black boy, um, in the inner city, [00:04:00] in the capital of New Jersey. And I was going to inner city public schools during the crack epidemic. And, they were medicating and bussing, a lot of young Black boys, um, out of these public schools and into these special needs schools, some of which, uh, didn't need it, some of which, which may have needed it.

But a lot of it was, you know, encouraging, you know, parents to get a check. You know, if you look up preschool to prison pipeline, there's a lot of that in there. And my mother wasn't having it. And so she was really about, uh, finding different solutions. A, uh, lot of tenacity, my mother, uh, worked three jobs.

Uh, so often, uh, two jobs, three [00:05:00] jobs, uh, went to school, uh, raised three children and got three degrees, four now. Uh, um, and so my mother has, uh, you know, overcome a lot and it was for her, I did, she wanted me to be more tenacious. Um, which I always say is, is good and bad. Um, um, finding ways around these medical solutions, you know, would take me, I'll be 35 in August.

So, 34 years, uh, and the solutions never worked. And so, what we found, what I ended up finding was these, I explained it to my friends in this way. I've been swimming upstream for 34 years. And knowing that something was off, feeling it in community college, that I needed to be tested. Something is off.

I knew I needed more time during exams and tests. [00:06:00] Um, but too proud to have another label. I was already hiding one secret. Which was my sexuality. So having another label or being othered in a different way, was, was something I was afraid of. And, and what is that gonna mean about me? Because what did it mean for me as a child growing up?

I didn't wanna be othered. Um, although, my experience as a child with, uh, autism level one, formally Asperger's syndrome, it, it was definitely othering in every, every form. It, it's been described as children with, uh, uh, autism level one are, um, like aliens who have come to this planet for the first time and are learning from their experiences with everything.

And so they hear everything. They see everything, they feel [00:07:00] everything. And that's something that also, and, and it's also been called anthropologists, little anthropologists because of the, how we're experiencing the world. And so that was my existence, and I always knew I needed help. I came to that point again in college.

Well beyond community college and my four-year institution, also came to that point, began to get tested, graduated, um, never finished, knew again, once I entered the work world post-college bubble, that I needed to be tested, went to a psychiatrist and was told that I had PTSD and major depressive disorder and it was situational depression, essentially, because my grandfather was dying, my sister was in an abusive relationship, and I was going through it with everyone who was close to me, most likely because of my Asperger's syndrome. And so, um, there was a lot going on in my life at that time, and she [00:08:00] diagnosed me with depression.

And I remember the moment she said, how often are you sad? And I said, every day, and that was when she, I knew that she had, she had made the diagnosis of something other than what I might have been there for. But one of the things she said to me that stuck in that, in that session, was most of your issues don't involve you, they tend to involve the way you react to other people. And that is something that carried with me into my current therapy life. And so, uh, quickly, and I'm gonna wrap this answer up. This is the shortest answer I've ever given, but I, um, last August I began, so I have a nephew who's diagnosed autistic who went to, who grew up going to that special school that they wanted to buss me to.

He is, he was diagnosed autism level three, um, as a small baby, um, and has done the sort of, [00:09:00] I don't know if you call it miraculous thing, but he's moved along the spectrum. Um, he doesn't hold information as well, but he does, he is speaking, and he can take care of himself. He's fully, you know, uh, he would be considered, I presume high functioning in, in the fact that he doesn't need as much care, I presume.

Um, but he, long story short, I was, we were together in a Walmart. He's always around me, and he actually uses, he does the thing that I've always done that I didn't know I was doing, which is he watches my every move and mimics me. Because he is presumed that I am some, someone to mimic it. It's my jokes, everything.

And so we're in a Walmart, and he is staring off into this thing with all these lights. And I found myself, because I was incredibly anxious at the self-checkout. I found myself, um, yelling at him [00:10:00] and I was yelling at him for, and I heard myself and it was the same thing that my grandparents used to yell at me about.

And it made me nervous. I didn't say anything to, at all. I started, I found randomly on the for you page, somebody on TikTok was talking about it. And I said, oh, nah. But then the more I started to think about how they wanted me tested and all of that. And I started asking my mother questions and my mother's always talked about, she calls it, that thing you do.

And it's it's, um, I go inside of myself kind of thing. And then I start twiddling my fingers and I can't hear people who were calling me. And so she took me to doctors when I was younger. And a lot of the doctors that I went to felt a lot like her, um, which is all these kids would being overdiagnosed, let's find different solutions.

And [00:11:00] so, yeah, I asked my mother questions. I took all the available autism exams online multiple times. I even tried to change my answers a little bit because I was trying, I was like, nah, it's, I'm doing it wrong. I don't know. I tried to change my answers. It didn't work. I still scored extremely high. Um, and I was like, this is weird.

Like, because I see myself as someone who has accomplished and, and survived so much, but then I really started looking at the fibers of my life and the fact that my life had essentially, that I've been going through with a lot of Black femmes, uh, queer people, Black women go through in their late thirties, mid to late thirties, which is something called burnout, being a high achiever, and then having this boom, kind of burnout feel.

And I'd been going through that and put it all together. Then I started this job with the government, got good insurance [00:12:00] of course, found a center that had a therapist and a psychiatrist in the same space. I had the resources now to, you know, do what I needed and the, the most beautiful part of my experiences is I was believed. I was believed and I was heard.

And as a Black person in a larger body, Black queer person, non-binary person, um, always with a fresh set of nails on and sometimes with a fresh face honey. And so, I am being heard in a medical situation, um, was abnormal for me, but it was, it's been a beautiful experience. And so from there, there was different types of testing.

I had done neural tracks tests where they test the way your brain works and holds memories and all that shit. And so, yeah. And my insurance paid for it too. I mean, that's, that's, that's, that's what the, the, [00:13:00] the government does. I was like, oh,

Danielle: Really? Whoa. I am happy for you! I am so happy for you.

Richie: So I had a bunch of stuff and so it it's just been, um, a really interesting journey.

Lastly, it was also fulfilling. It was incredibly fulfilling to know that I'm not fucking crazy. Cause I always thought I was like, something is off and, and I didn't know what it was, but I'm like something is off. And then there was these moments where people would say, why are you like that? My whole life I've always heard, why are you like that? What's wrong with you? And, and so I would, what I would do again would just shift. I would shift, I, I I'd adjust the persona, cause most likely I was operating through a mask. And so I'd adjust the persona to be more likable by observing everyone and everything in a room. Down to how people cross their legs, down to how people [00:14:00] move their mouths, how they randomly might scratch here on their face. Um, as a very natural part of it. And essentially, I was method acting. Really, to survive.

Danielle: I mean, I think, I think that's such a good way of putting it method, acting, I think gets at it better than how I've heard it described by other people is cause you're all in, like you're all in on trying to be that person that people want you to be.

Right? And, and I think there's a difference. When I look at my life, I'm like, I never thought I was masking. I, and I actually didn't think there was anything horribly wrong with me. But as I grew up within white evangelical Christianity, and I took it seriously, so I became a missionary, cause that's what you should freaking do if you literally believe people are going to hell, you know, whatever. Uh, and then I started to be like, there's something terribly wrong with this religion, this religion that my community has given me. There's so many gaping ethical holes. There's so [00:15:00] much hypocrisy. There's so much not adding up, and y'all are supposed to be the ones that also are obsessed with God. Like I'm so confused. So I started to be like, there's something rotten with this system. Then as I got older, I turned that to myself. Right. And I said, there's something horribly, horribly wrong with you. So I, I think some people have had that sense of there's something wrong with me, their whole life and other people maybe don't have the insight.

Maybe I didn't have that insight until much later in my life, but either way, it sucks. I would not wish that on my worst enemy, you know, to think there's something wrong with you to that extent. Yet people who think like that often find solace in religion. Yeah. Cause like, isn't that one of the tenets of like fundamentalist Christianity is they affirm that core belief.

That you're a sinner at your very heart. Yeah. And you need an outsider to tell you how to be, right? How to act, how to live. So I'm sorry, I'll be done talking now, but I just wondered if that sparked anything with you and how you saw masking maybe show up [00:16:00] in religious spaces for yourself.

Richie: It did, you know, um, like you said, I never thought I was masking because I was, I believed I was neurotypical.

I knew I was different from other people, but I didn't think I was that different. I'm just trying to, I'm trying to do life like everybody else. I, I would be 34 years old when I realized, is that really you? Or what, do you really wanna do that? You know, I was, you know, having this moment of like, is this you, or why do you do that like that? Or why do you, where'd you get that from? And, and realizing I picked up things from other people and then just constantly putting it all together. But watching myself, you, you mentioned, uh, one, you mentioned becoming a missionary. It’s funny, uh, I originally went to Bible college, and I talked about that a little bit on the other podcast that I did.

Uh, I went to Bible college. Pentecostal [00:17:00] Bible college in the middle of nowhere, honey, about 45 minutes outside of Detroit, it was in a little town called, uh, Auburn Hills, Michigan, and I wanted to be a missionary. Um, uh, and I took everything very seriously from a very young age, locking myself into, in my bedroom, reading the Bible, using dictionaries, um, you know, Strongs and other concordances.

Danielle: Oh gosh, I know I've done that myself.

Richie: You know, I'm in there, I'm, you know, I'm memorizing the verses. I'm knowing how to jump, you know, and in church I'm taking notes, I'm watching people. I am, everything's literal for me. Everything is real for me. This, the longer I stayed in that room, the more this God became real, the more this thing became huge.

And the more it controlled everything that I was. And, um, yeah, I, [00:18:00] I didn't know that there was like, that I was putting on a mask. I thought I was going deeper and deeper in God. I didn't realize that, that I was becoming a thing, uh, entity within this institution. I just, yeah, I didn't see it that way. And, um, I had souls to save.

I was a, you know, evangelist of the month, often I was, I would bring in a lot of people. Um, in the United Pentecostal church, we used to, we baptized on site. So we did baptize people in the name of Jesus Christ on site. You come to our church, you say, wanna get baptized. You are not waiting until the first Sunday.

Okay. You are getting baptized tonight. We got a robe for you. You take off everything, put on this robe and go in the water. And we used to baptize in a horse trough, um, that sat on the side of the building and it was ice cold water that stayed in there all year round. And so, [00:19:00] uh, we took the people down in Jesus' name and brought 'em up.

And then often we prayed them through till they spoke in some kind of tongue. Okay. Cause you got to come through. And you gotta know that you know that, you know, and so until you hear yourself speaking in tongues, you ain't got nothing yet. Come back tomorrow. And so that was, you know, my very much my experience, but I, um, uh, yeah, when you, when you say it, it's funny knowing about masking now and thinking about it.

In retrospect, because everything in me feels like, oh, that's not a mask. And my therapist calls it a mask too, but everything in me is like, oh, that's not a mask. I was, I was this person that was, that was my thing. But if I say that it's a mask, then somehow it invalidates the severity of that time period for me. The church as an institution changed my [00:20:00] life.

And it gave me a purpose when I otherwise had none, had it not been for the, uh, the Black church, had it not been for the Pentecostal church, for the little Baptist church I started, well it ain’t little it seats like 4,000 people. But I started in this, this huge Baptist church on a corner, not 4,000, maybe a thousand.

Um, but I started in this Baptist church called friendship Baptist church, 111 Perry street, church, New Jersey. And, um, that was the first church I went to. Um, and it's where I confessed my faith. And, but the institution, as it, as it was, saved my life. I did not have a purpose, I felt. I didn't know where I belonged in the world.

And I knew that nobody liked me as I was. Um, and I had been through, I'd experienced a lot of trauma, [00:21:00] very, very early on and survived it. Um, domestic violence, abandonment. Uh, rejection, um, uh, bullying. So, I didn't belong anywhere. And so when I walked into this place, I knew that I could hear good music, I knew that I would feel that thing that you feel when a church was rocking and you know it, and I knew I would feel that. And I knew that regardless of, if anybody in this building knew who I was, I was gonna feel that again. And so, I was chasing that. And, um, but when I say it saved my life, I would've been dead, probably. Especially the sense of purpose that I didn't have.

I was alone a lot. My mother, I was a latchkey kid. My mother worked a lot. Um, and my, you know, and so I [00:22:00] was alone a lot and I don't know that without the church that I would be here. Um, just given all that was my life before that, but it gave me something to try to be. And in that, yeah, it was a mask, yes.

Being 13 years old, coming of age, but then putting on the identity of a preacher and all that that was supposed to mean. Big shoes to feel filled, going into high school with these same shoes, preaching, teaching, singing, traveling, having a calendar, being this little dynamite preacher that everybody knew and, you know, having all of the colloquialisms down.

Cause when I came to the church, I wasn't churched, so I didn't know. But again, you know, you're, I was at home building that mask, you know, I was at home getting it together, learning all the [00:23:00] things you say, you know, to get people hype when you don't know anything else to say, you know, because in a Black church, if I grab a microphone, I mean, to this day, it's, it's down, pat.

I literally, I still got it. It's, you know, I grab a microphone and I say far, I reckon that the sufferings of this present time are not worthy to be compared to the glory which shall be revealed in all of us, come on, somebody. Literally, and the whole place gonna go crazy. But that's what, you know, getting all of these things down, you know. For God is the greatest power and we shall not be defeated. These things, and you learn these things and you act them out.

And, and like I said, it didn't feel like it wasn't natural to me because I became it. Method acting. I became it. It was me. It was my life. It was my story. But somewhere around the 11th grade, my sexuality kind of couldn't be curved [00:24:00] anymore. And then I wanted to cuss. I liked to cuss. I'm a good cusser.

I enjoy it very much. And so, uh, I, I wanted to cuss a little bit, so I had a friend whose house I would go over. We started out as prayer partners and then I realized he was a little worldly. And then I said, well, we gonna be prayer partners, but we, we could be messy partners. And I used to go over his house and cuss.

Um, and he was probably the only person in high school that knew that I cussed. And so he, you know, I wanted to experience, you know, some type of connection, physical connection. I wanted to do things that teenagers were doing, and I was tired of not watching television, not going to the movies, not believing in this, not believing in that.

And that started to weigh on me. And then I found myself not wanting to sit in a pulpit anymore, and I found myself not wanting to preach anymore, and [00:25:00] wanting, feeling more and more unholy. The more you go into fundamentalism, the more of your righteousness is filthy rags. Uh, and so much of it is pertinent, right?

So much of it is, is literally like it is, it literally keeps the religion going because you need to feel dirty. You need to, you need to need their God to make you clean again.

Danielle: Yep. Yeah. Um, and only their God.

Richie: Yeah. Oh, absolutely. You need the alter calls, you need all of the crying, and the, the, oh, my mother used to say to me, cause my mother is, uh, Sunni Muslim.

Um, and so my mother would say to me, why is it that when you pray, you sound like you are in, uh, pain. You sound very miserable when you pray. And I [00:26:00] was like, whoa, but I did. And I did for years, you know, there was so much misery, so much shame in everything that I knew that I was. And that was the biggest thing for me.

It was very, uh, rough. Um, but it, it, it's, it's definitely one of the reasons why fundamentalism held me for so long. Um, and then I went to a four-year institution and majored in political science.

Danielle: Oh, do, oh my gosh, you just, you totally broke some of the rules, but if it's okay, I just wanna say a few things I heard you saying.

Um, and one is, I love the complexity you bring to this, because you talk about how it's been positive for you and how it has also harmed you. Like literally every part of your story that you've shared with us thus far, I can hear both of those, like at every part of your [00:27:00] story, right. Is like, there's pain there, and then there's also resilience. And, and so I just, I think it's really helpful to take a step back and say for those of us who found parts of our identity in religion and being really good religious people, um, it's not all bad, but I think you've already kind of articulated what can happen when this identity we build, we start to actually become aware that we feel differently inside than our public face is now presenting. Because I think that's a really common thing for autistic people. It's we do believe it. We believe it way more than everybody around us, which causes some confusion inwardly and internally.

Right? And then what ends up happening? And you already mentioned this, you already said this. What ends up happening is you are an all-in true believer method actor, trying to fit in. Take it seriously. And then you end up finding yourself exploited by this institution. Whose end goal is to keep [00:28:00] the institution going.

That's the end goal. And it has taken me 38 years of my life to say, that's literally the only end goal. My dad's a pastor. I was raised a pastor's kid homeschooled in the fold, tiny. My mom was charismatic. So I'm really tracking with all this, some of the Pentecostal stuff you're saying, you know, but I'm just like to find out that that's the end goal.

It's really hard to then go back and look at your life and say, but it did help me, but it sucks now to kind of have some of these realizations. So I just heard some of that. Oops, sorry, in your story. So I just wanted to, uh,

Richie: I just kind of, I actually got emotional thinking about it because we often don't talk about, I, I describe my, um, autistic experience as living in a bunker with glass walls.

So I can see the world around me and they can stop by and see me, but I am often, not now, I I've done [00:29:00] a lot of the work, but, but I was often very alone and, and felt trapped like, and no one could get to me. Um, and not only was I in Plato's cave, but I was also the one performing the shit on the wall.

Danielle: Woo, that's a metaphor, ok.

Richie: Oh my, yeah, I was, I was in there and I was also the one doing all the flickering and being a part of the show, leading the show often, but, and realizing that it was a greater, uh, and believing that there was a greater purpose for all of this. Um, and I, I guess the perfect transition would be when did you stop believing that?

And so for me, um, when I went to college and I, and I, so I got involved fairly quickly. So I was, I became a political science [00:30:00] major. And so I got involved with this club. Uh, it was called the political science club. And then, um, then I got like made into an officer. I got elected president and then really fast in my first year at this four-year school.

And then I started spearheading uh, you know, the model UN. And then from there, I ended up meeting these kids, um, that were a chapter of the democratic socialists of America. And they did a lot of work, a lot of activism, on the ground outside of campus, on campus, starting unions, getting people unions, workers' rights.

Um, we got the New Jersey dream act passed, which is, uh, allows for people who are not citizens to not have to [00:31:00] pay out of state tuition. Um, you know, and they can actually qualify for some aid and some help. Um, we, we did a lot of work on the ground in that group and, but they were all atheist and um, but they were active, tremendously active, and I got involved with them.

I became the anti-racist, uh, issues coordinator for the democratic socialists of America. And, you know, just continued a lot of that work. Um, but I was also taking high level 300, 400 level courses that were challenging me, being taught by Ivy league professors. And I was being challenged regularly to think critically, but I knew that didn't fit the formula.

Because I had to keep my brain in a space [00:32:00] where my academic mask would not interrupt my Christian mask, because my Christian mask was what I thought was the glue that was holding me together. Because who was I gonna be without that identity? That's all I had known since I was 13 years old. And at this point I'm like 23.

And so, I am like, I gotta keep this on. And I had this teacher who would call me her, her, uh, religion expert. And whenever there was, cause we were learning about the enlightenment period. And so we're talking about when they started challenging the authority of the church. We're talking about, uh, Thomas Hobbs The Leviathan, and we're talking about Nietzsche The Will to Power, Karl Marx.

We're talking about all this whole entire era where it's like, you know, fuck the church. You all, can't tell us what to do. You know, it's kind of like separation of church and state. There's this development of ideas that is [00:33:00] coming up. You know, the printing press is here, and we are, you know, there's all this development in art and music and everything.

And so I'm studying this period. And I remember it came a time where I couldn't, I had to, to think critically. and I remember I was sitting in the class and as I, cause we were reading the direct sources, like all those books I named mm-hmm we had to read those books. And so I remember I was sitting in the class and my brain popped like a rubber band.

Like when you break a rubber band just popped. And I said, something is happening to me. Something is happening to me. My mask broke. And that's what happened. I think my mask broke. And I started to not believe it. And that was the first. And I thought to myself, this can't be no, no, no, no, no, it can't be, it can't be, it can't be.

But now I was like, in my head, I'm like, religion is the opiate of the masses. It is the sigh of the oppressed. [00:34:00] I am, you know, I'm quoting Thomas Hobbs. I'm quoting all of these things about how the church and the institution does not have power over me and how I, and I'm like, whoa, my mask is cracking.

It's shattering like piece by piece. I leave class. I didn't even like wait for any friends or anything. I leave class. I run to the library. I find an empty room, a study room, and I kneel down in the corner and I just weep. I weep because my mask is breaking. I don't get to be in this place. What is happening to me?

I'm broken. Well, I cannot believe this, this, this, this, it has to be right. It has to be, I can't question this. And then my, like I said, all my friends were atheists and I'm like, oh my God, these people have corrupted my spirit. And then I start, I remember finding [00:35:00] cause again, I'm trying to, I wanna know stuff.

So I find this book, the God Delusion by Richard Dawkins. I try to read it. I couldn't read it. I try to go through it. But there was something that stuck with me. It was the beginning of the book, his lyrics of Imagine. He says, imagine all, you know, imagine there's no heaven. Imagine there's no hell.

Imagine, you know, there's no God, essentially. And I'd be like, oh my God. And I started to imagine it. And I felt the emblem of peace and it scared me. And I just continued in a panic for the next few months, I ultimately had a nervous breakdown at 23 years old. I felt like I was going to die. I ran back to the church, got rebaptized.

I was like, oh no, I gotta give my bad life back to God, I can't be this way. And had a whole just meltdown for a while after that. But it just more of my mask began to break, cause there was also the mask of [00:36:00] heterosexuality and that's,

Danielle: Oh my gosh. All of, all of this happening at the same time, I feel like is so overwhelming.

Richie: That's why I was going crazy.

Danielle: I wanted to ask you a question about, you know, having a nervous breakdown because I think this is kind of a hallmark of what causes undiagnosed people to finally seek a diagnosis, either self-diagnosis or through the medical establishment, is like getting to the point of, of literally having nervous breakdowns.

And, um, I wonder if you kind of think of that now, as you look back as like, that was autistic burnout, that was, cause I, I start to think of myself, like I would always joke, like I'm always having an existential crisis. I was like, yeah. That's, that's like an autistic meltdown internalize, right? I don't flat my arms and I don't shout at people.

I learned early on if you're socialized as female and you need your parent to love you, you shove that stuff down. And you take those, you take those meltdowns inside. You know, you [00:37:00] take them on yourself. And so that's, I'm just wondering if that's kind of how you would even see that now.

Richie: They ruin, they ruin your body, your nervous system.

Danielle: These existential crises are real. That's another thing that people think people don't understand about autistic people is the existential crisis, crises we are always having. Because we're thinking about patterns, we're thinking about systems, we're, and you intrinsically knew this is the other thing, autistic people actually can't, we don't like to be false.

We don't like to lie. And so you are having this meltdown in part because you're like, I don't think I believe this anymore. Therefore, I can't perform it. No more method acting for me. If I don't actually believe it, I'm gonna lose relationship and community. And so maybe I'm projecting. Maybe that's not what was happening to you.

Richie: Um, I don't know if I was thinking about community very much. I, I, I know that I was thinking about, I would have nothing. Cause remember I was alone. I was alone.

Danielle: And, and so [00:38:00] those are the ties that kind of keep you performing, but I don't think we're very good at performing, honestly, if we don't feel it.

Richie: No. Especially when, you know, when the jig is up, that was a thing. The jig, the jig was up for me, and I did go, I went full body, mind, spirit back into the church. I prayed through again, I got my tongues back. I got baptized again. I fasted, no food, no water total fast. Um, I was really just, and, um, I, then I had some illnesses that came up.

Like, you talked about that physical part of the body, that breakdown, it did turn inwardly. And my nervous system was shot. I used to have these unwarranted, sudden movements like that. Because my nerves were so bad during that time. Uh, like I said, panic attacks every day. That would bring me to my knees.

I was [00:39:00] losing my hair. Oh, I lost 70 pounds in a month. Um, I was truly, truly going through a literal hell. Um, I believed literally that this God was coming to kill me, that he was going to destroy me because I had lost my faith. I, I believed that there was no grace for me, that I had fallen away.

Um, it took me months. It makes me very emotional, the hell that I put myself through. I, not put myself through.

Danielle: Yeah. Don't blame yourself, please.

Richie: It does make me very emotional, because yeah, it was literal torture and I had no one to help me. You know, but if I started talking to my mom about it and she would be like, don't believe that. God is graceful, duh, duh.

If I tried to talk to my friends who are still in the church and they would say, God forgives you. And [00:40:00] you know, a lot of times autistic people have issues with forgiveness in general, because we, uh, have a tendency to view everything as intentional and diabolical. And we, I would never do that to you, so because you did it to me, it was intentional.

Cause everything we do is intentional. And so it, it, everything we do is direct and intentional. So now you, why would you, so I believe that God was looking at me and said, you did that on purpose and you, and you did that because you wanted to be in the world. You wanted to match your friends and now you've missed out on heaven.

Um, but that time period would plant a seed that after all of those next months of fasting, praying, absolute fast, the panic attacks stop. Um, I got some skills under my belt. That's when I started my therapy, my adulthood, during that time, got some skills [00:41:00] under my belt to tense my nerves and release and tense, my nerves and release.

You know, and my nerves stopped. I stopped shaking. I found a herbalist online randomly one day during this time, where I started to, I had a stomach issue that had developed where my body was, uh, not producing enough acid, and to digest my food, which then threw off my electrolytes because I wasn't getting any nutrients from my food.

And so then it caused heart palpitations. So all of this is making me panic even more. And so, but I, all this starts to heal and I'm back in church, you know, I made a vow to the Lord and I won't take it back. And so here I am, I'm back in church doing the thing I gotta do. I almost quit college.

Um, I barely made it through the skin of my teeth through all of that, but I made it, made it through that year was still in therapy, doing it all. I was doing [00:42:00] yoga. You're not supposed to do that and holiness, but I was doing yoga because it was bringing me peace. And, um, I was doing all my meditative stuff.

And then also, you know, going, doing my church stuff over here and I was fine. I was fine for a while until that next summer. Um, I was getting ready to go back to school and I would still wake up every morning around six o'clock to pray. And this morning in particular, I just had a conversation and I said, you know what, God, and that's when this is me, me coming out to Jesus.

Uh, I'm gay. Mm, yep. Mm-hmm, and I need to say it. And I wrote it down. Actually, I was writing, cause I wasn't talking this morning. It was too quiet, and I didn't wanna disturb that quietness. And so I started writing free form and I just wrote I’m gay. There's nothing I can do about it. It's who I am. And what if it's just who [00:43:00] I am, and that was it.

And then I called my girlfriend at the time, told her we, she cried and, and got all in her ego about it. But that moment wasn't about her. And then I just swallowed it. Because it didn't match what I was supposed to be. I had now promised this God that if he didn't kill me, that I would, I would, I would be, I would be holy for the rest of my life.

And, and so I then start to get really, really depressed again, because I'm lying and now I know I'm lying cause now I've just come out to myself. And I've just come out in prayer. And so now I'm, so I had a friend who was going through a pledging process. It was really dark, dangerous time for him.

And he was sad and because he was being tortured to death, literally, and I was being tortured to death and we had a, a moment of, uh, where I cried and I told him, I think I might be gay. And he looked [00:44:00] at me and said, I don't care. I love you. You're my friend. And I'm always gonna love you. Don't change nothing for me.

And you know, and then, so I swallowed it again. I had to write a paper, by this time I had added English as a second major, cause that poli-sci shit was making me critically think too much. And I was like, all right, I need a second major to throw this off. I'm writing a paper for my English class. The characters wouldn't work out.

And I was like, it's something said, you've gotta tell the truth or you'll never be able to finish this story. And I'd called this guy, this, this cute Filipino guy that I was cool with at the time we didn't even know each other. And I knew that if I came out to him, he didn't know anybody and he didn't know enough people.

He didn't know who I knew, so he would never tell anybody. So I just needed to come out to somebody who was a stranger other than me. And, and I told him my whole story. And [00:45:00] then I said, huh, I'm just gay. And he was like, how do you feel about that? I was like, I feel damn good. But it didn't stop there. I picked up the phone and texted my mom, my sister, the family group chat and told them.

And then I started telling people I ran into in the student center who I knew, you know, I'm gay, right? You know, I'm gay. Yeah, I'm gay. Yeah. Me. Mm-hmm. And people just would be like shock and they would be like, oh, well, thank you. And then somebody started crying and then we started crying together. I can't remember who that was, but I just felt like a weight was lifted off me when I told them, and then I just kept telling people.

And, and then I couldn't, that's when it shook up. And then, you know, as I talked about on that other show, which you all can go and listen to. Um, but, uh, yeah, I, I talked about all of that long story short. My, my [00:46:00] pastor's son was gay. Came out to me, got found out by his father's father, beat him, fractured his ribs.

Uh, and at that moment I had decided I was going to be an atheist. I was like, I'm done with the church. Don't want nothing to do with it. It's dead for me. Over it. Never going to church again. Um, but that, wasn't the, the way for me to resolve that. Um, and I couldn't just be an atheist and it just didn't work that way for me.

And, and, um, but yeah, I struggled for a while, but yeah, coming out was that sort of door of like taking off another mass began to break. It began to break. And, and, and I was like, damn, I think I've been peeling off masks since 2011.

Danielle: I mean, I think that's, what's so fascinating about your story is like you have had practice in unmasking and you've had the practice of having [00:47:00] to weigh that feeling of freedom, you know, you would get from telling people versus, you know, the reactions people have and all of that. So, I just think there's so many parallels in you. There's such an overlap between, you know, queer and autistic communities that I just wanna keep learning from and exploring, but I think there's also some overlaps there around masking and around finding who you truly are.

And that's what, you know, when I listen to you talk, and when I listen to your podcast, you know, there's a depth of, um, thought to what you say, because I feel like you've had to do this work on multiple levels, you know, and you've had to do it your whole life. So your, your well is very deep of the stuff coming out of it.

So I just wanna say, thank you, you know, I, we have to wrap this up kind of quick, but I, I just wondered if, um, just from listening to your podcast and I really encourage everybody to go listen to it. Um, Surviving Fundamentalism. You [00:48:00] kind of, from what I've heard, you, you still are a person of faith. How would you kind of describe that for yourself?

Richie: Some days I am, some days I'm not okay. I am, uh, I have accept, I'll say this much. I, um, I've accepted that there are, there's so much to who I am and you don't just kind of take back your journey. And so, yeah, there's a part of me that's very, very churched. There's a part of me, you know, remember I, my community, I was in a, you know, in fundamentalism, um, being raised by preachers, deacons, church mothers, um, and, and, and, and I was in a church finding community and I was going alone.

So that was, uh, [00:49:00] torturous, but also interesting. Um, and I was finding that, and finding that community, um, it saved my life, but it also fucked me up a lot. And it fucked up the way I saw myself continuously, because in, in Pentecostal holiness, you are often being stripped. You're often being, just having your skin just, just, just pulled off and, and it's just like you're being stripped and there's nothing, no part of you that's good enough. There's no part of you that's acceptable. There's no part of you that is good enough for your God. And in having all of that and continuing to go back for more and that being very much a part of my life. Um, yeah. Um, [00:50:00] but, yes, I, I do agree with you. There is a, a very, a very deep well here, but I, I wanted to say, um, we had a little conversation off air before we started about self-help and there's so much good in it.

There, it can also be bad, but I used a lot of self-help book, a lot of, uh, you know, the books that the preacher sell from the Christian bookstore, you, the Battlefield of The Mind, Joyce Meyer and you know, Naked and Not Ashamed, TD Jakes. And you're reading all these books and you're highlighting Matters of The Heart by Jaunita Bynum.

You're highlighting these books and you're just in it. They're like next to your Bible. Sometimes I used to put 'em in the Bible case while I was reading them. Good morning, Holy Spirit by Benny Hinn. And I've read all them books, but I, also was reading a lot of self-help books, you know, The Power of [00:51:00] Positive Thinking for The Teenage Soul.

Um, you know, all of these things that I was engaged in trying to make myself better, trying to improve myself. Like I said, I wasn't always this good of a speaker. I used to read aloud to make myself, um, you know, kind of dot my Is and cross my Ts. And I would read aloud very slowly and make sure to ennunciate my words.

And then I was also listening to a lot of preachers and I'm taking in that sound as well. So that's where a lot of that rise and fall comes from. You will not get monotony with me. Um, but that's where a lot of that comes from. And, um, I used to lock myself into my room and do that, but then it just switched.

So when I got older, it became speakers, authors that I liked. Maya Angelou, uh, Toni Morrison, [00:52:00] James Baldwin. These were people whose speech patterns, I would watch these videos on YouTube and I would learn, I would say to myself, unconsciously, uh, intellectual people do these pauses when they speak, they go, ah, uh, uh, uh, uh, and then they say something really profound.

And so I, I used to do that and I would write down these quotes and I would pause the DVD to write the quote, and then I would put it into different parts of speech when I would speak. So then I knew that if I said it this way and I folded my hands and I sat back and I scratched my nose, that I would be too deemed intelligent.

And all of this was unconscious. And I did know it, and it wasn't until I started revisiting it in therapy, there was a reason I brought all of this up. Um, and, and, and because the thing about, uh, diagnosing, having these harder conversations, is that everything now must be rethought. [00:53:00] Everything must be redone.

There's some episodes of Surviving Fundamentalists where I am completely weeping over the realization that I am neurodivergent and how much it has been so exhausting, uh, in my life. And so, yeah, there's, there's all of these things, a lot of that self-help stuff, and a lot of the stuff I was learning, all the work I was doing in therapy and all the Oprah and the Brene Brown, and all of these things have now got to be rethought because it had nothing to do with me.

And it had nothing to do with the fact that I was, I, that I, it, it wasn't that I was a bad person, and it wasn't that I needed to correct this and correct that. And so when I talk about swimming upstream most of my life, there is something that, and I'll say this, and I'm done. I promise, I'm not gonna Black preacher you all, I'm really gonna be done. But, um, [00:54:00] my nephew asked me the autistic one. He says to me, um, do you think I'm stupid? And I said, no, where no, where'd you get that from? He says, I don't know. But they say that I am. And he says, do you think I could get a job? Like a regular job? I said, yeah, I think you can.

I said, these are your strengths. You should look for a job where you can use these strengths. And he goes, thank you. I couldn't tell anyone this. And then he says, and that was probably the first instance where I should have thought something. Cause I began to weep at work. There was some sense of familiarity, like a button that went off, but I didn't know what it was.

And I was so triggered, and I said to him, you're different. You think different, [00:55:00] you have a disability. And what that means, I said, one of the hardest things is that you were raised to believe that nothing was wrong with you. Ain't not wrong with you. Go out there and play. And what happens is you're out there playing, you're in the classroom with these people, you're doing the things, but you know something's different about you.

You can feel something's off. It might not be anything noticeable, but if you, even if you can't feel it, them other kids gonna let you know, you don't run like us. Why you weird like that? Why you do that? Why you do that? Why you talk so loud? Why you funny looking, why you do that? And they're gonna let you know that you don't fit and it, and, and there is like, but you're still, you're still running.

You're still playing. You're still trying, because you don't know that anything is different about you. And so it's, it is, it fucks you up, but it makes you stronger. [00:56:00] And so I, you know, Maya Angelou says I wouldn't take nothing for my journey. I don't think at this point that there's anything I can do about it. I'm powerless over it.

Um, so no, I wouldn't take anything for my journey. Wish I had the resources, but I didn't. Um, and so with, with, with this kid, it really made me look at myself and go I'm, I'm all of these things because I've had to swim upstream. My entire life. The well is deep because I swim upstream. I was learning, I was reading all of these books.

I was taking all of this shit in. I was experiencing life, but the thing is, is now I'm like a baby. I thought I was a baby when I came out again. Um, but I, I'm like a baby and I'm so new. And having this understanding, [00:57:00] I'm walking through the world unasked. In in, in, I'm unmasking and I'm, and I'm, and, and it's difficult because you're trying to explain people to people who've known you for 15 years. My friend said to me the other day, why, what you mean? You anxious? Where's the bad bitch at? You are the bad bitch. Why, what you, ain't never been anxious like this. And I said, it was a lie. It was all a lie. I said, it was all a lie. I am terrified. I walk through the world, terrified every day.

I just did it scared, but I was terrified. I said, do you know that my hearing on the inside of my ear is amplified. My eardrums are incredibly sensitive. My sense of touch and feel is amplified. My, my, it literally is sometimes so loud [00:58:00] and even there's not even much going on around me. And so I'm, you know, I said, I don't like to go places by myself.

I don't. Cause I was talking about going into a car dealership. Because was trying to buy a car and I was just like, yeah, I don't wanna be alone. I don't wanna fly alone. That's why I haven't been on an airplane since 2006. And you know, I'm, I'm terrified of change. And I start, and he was like, I never knew this about it.

Like I be your best friend and I've never known it. I said, because I've been masking as a bad bitch forever. And I'm just telling you, I walk through this world afraid every day. I just never showed it because I couldn't as somebody who was beat up by entire classrooms of children, I couldn't. My father, uh, beat the shit outta me and my mother. I, I couldn't be weak and that was [00:59:00] weakness. And that was what I was avoiding. Every single time I got close and was like, I ain't gonna do it. I'm not, nevermind. It didn't work out. Oh, well just, nah, I was avoiding that because having another intersection, what was it gonna mean? You know, I still, I had a meltdown at work the other day.

I started crying and calling my damn self stupid, uh, because I was struggling, but you know, didn't, I have to have conversations and talk to myself about who I am and how much I've overcome. And so, yeah.

Danielle: Wow. Mm-hmm okay. So like everything you've just said, the more I hear from autistic people and their stories of survival, especially like I already said, queer autistic people.

I, I have these dual sensations, right. When I hear people share their stories, one is just awe, like a lot of awe at how [01:00:00] you've creatively, you know, adapted, survived, masked and all that. But also it's like, when you talk about masking, you're actually talking about trauma work. And when you invite other autistic people who, maybe diagnosed or not, to start to consider the ways they've masked in order to receive community and love and a sense of identity, right? Mm you're asking them to do trauma work. So it's really deep stuff. It's really deep stuff. That's what we're trying to talk about a little bit at, at my, you know, community, but I just wanna tell people, um, they can find you doing the work of inviting people into your unmasking process in your podcast. So I let's, again, like shout that out, Surviving Fundamentalism. Is there anywhere else people can find you on the internets that you would like wanna direct people if they wanna keep hearing from you? Um, cause you have a lot to say, I'm sorry we have to cut this off, but like I'm so glad you have your podcast.

Richie: There's so much there. You all can get into, especially the first few episodes. It's just like the first five episodes are just like my life story. So I'll just be talking about you go over [01:01:00] there, listen, Surviving Fundamentalism. And it's available on Apple podcast, Google podcast, Stitcher, most places that podcast are found.

Um, and so. Besides the, you stunned me with the trauma work. That's why I'm sitting there with my eyes closed, like damn.

Danielle: I’m sorry, that’s how I feel about it.

Richie: So that didn't even, I never even looked at the two, I've always considered trauma work to be something else, but absolutely, absolutely 100%.

Um, but yeah, so I am online, um, Instagram @Richieatitagain, uh, Twitter @Richieatitagain. Um, yeah, so, you know, you can find me there once again, and once you pull up the podcast for Surviving Fundamentalism, uh I'm uh, I mean, get into it. Like I said, there's some episodes of me just flat out weeping. I don't, and I'll say I don't have it to give, um, today, [01:02:00] um, because there was something I started there's, you know, as having been a missionary, you know, having been a preacher there's this thing, right. That thing that's still in your, like a, you feel like you have to give something to the people. You've gotta get it out. You've gotta get it done. And I think even on that show, is there's some unmasking in the middle of the show because I don't have it to pretend that I have this prepared episode.

And so sometimes we're just gonna talk about neurodivergence. And I've found that my audience mostly goes with me. Doesn't matter where, what I'm talking about.

Danielle: Well, I love it. I think you have already you know, blown my brain so many times, but you said at the beginning, like, you know, level one or, uh, what used to be known as Asperger's, you know, there's this, we're anthropologists and a ton of people who have found their way to God is My Special Interest have some sort of background in missions [01:03:00] work or cross cultural work. Like I literally have worked and lived in refugee communities for like 18 years in the US. And so all my friends are Muslims from various countries and there is something anthropological and now it's great. We can turn that attention towards like other autistic people and like you are inviting us into, so take your, I'm talking to listeners out, take your anthropological skills, you know, let's try to stop being colonizer. Let's just go listen to people, use our skills to just be interested and creative. And I think your podcast is such a great way to do that. So thank you so much, Richie.

Richie: Thank you for having me coming on here. I really appreciate it.

Share this post